Almost 20 years ago, I bought a Volkswagen TDI diesel wagon. The plan was to run it on the “Clean Energy” du-jour, biodiesel. Blue Sun Biodiesel, a local company, planned to build a co-op with local farmers to use drought-resistant oil seed crops as a cover crop to improve the farmer’s soil and provide seed oil to make biodiesel.

Local farmers are also hoping demand increases, as they are an integral part of Blue Sun's efforts. In 2002, Blue Sun started a farm program to bring local growers into the company to produce the seed crops locally and not import them from other parts of the country. At a series of public meetings around Colorado, the company initially found farmers hesitant about committing their personal resources to an unknown industry. In order to get farmers on the same side of the table, Blue Sun started a value-added farmer co-op that allows farmers to become equity owners in the company.

To buy in, each farmer must invest at least $5,000 (which goes toward equity shares) and plant up to 200 acres with seed that Blue Sun provides. In return, they sell the crop to Blue Sun after the harvest and enjoy a number of benefits that protects their investment even if they have a bad year. To undecided farmers, this arrangement presents a much higher degree of security by giving them three benefits to participate in the program: profit-sharing, equity appreciation and a revenue producing crop that fits in well with their traditional crops. There are currently two farmer cooperatives working with Blue Sun: the Progressive Producers Non-Stock Cooperative in Nebraska and the Blue Sun Producers Cooperative in Colorado and Kansas.

It seemed like a great idea. Unfortunately, six years on, they were still trying to convince farmers to grow the oil seed crops. They never did at any scale. In the meantime, they were importing soy biodiesel from Iowa to keep their pumps running. To keep a long story short, the energy balance of importing soy biodiesel to Colorado was nowhere near as attractive a scenario as the potential of local production of drought-resistant seed oil crops. For this and many other reasons, biodiesel for passenger vehicles never panned out in Colorado, or anywhere for that matter, and this, combined with Volkswagen’s ‘Dieselgate,’ signed its death warrant.

I say all this to point out that I’m intimately aware of the tradeoffs of “Clean Energy.” I bought a car to run on “Clean Energy,” but it ended up running on good old dino-diesel after biodiesel ceased to be an option.

I’ve been looking at options for a new vehicle, and while electrification is the future, I’m attuned to EV's potential downsides.

The five minerals most critical to EV batteries are each concentrated in just a handful of countries. For these countries, the EV boom holds enormous economic promise, but also environmental, social and workplace challenges that have yet to be addressed.

The Times recently had a piece on Norway’s world-leading EV adoption, outlining the ups and downs.

Last year, 80 percent of new-car sales in Norway were electric, putting the country at the vanguard of the shift to battery-powered mobility. It has also turned Norway into an observatory for figuring out what the electric vehicle revolution might mean for the environment, workers and life in general. The country will end the sales of internal combustion engine cars in 2025.

Norway’s experience suggests that electric vehicles bring benefits without the dire consequences predicted by some critics. There are problems, of course, including unreliable chargers and long waits during periods of high demand. Auto dealers and retailers have had to adapt. The switch has reordered the auto industry, making Tesla the best-selling brand and marginalizing established carmakers like Renault and Fiat.

But the air in Oslo, Norway’s capital, is measurably cleaner. The city is also quieter as noisier gasoline and diesel vehicles are scrapped. Oslo’s greenhouse gas emissions have fallen 30 percent since 2009, yet there has not been mass unemployment among gas station workers and the electrical grid has not collapsed.

Some lawmakers and corporate executives portray the fight against climate change as requiring grim sacrifice. “With E.V.s, it’s not like that,” said Christina Bu, secretary general of the Norwegian E.V. Association, which represents owners. “It’s actually something that people embrace.”

One advantage Norway has in electrifying is immense amounts of hydropower, second only to Iceland, and, ironically, a lot of government cash from exports of its large oil reserves, which can be invested in improving infrastructure.

Ms. Stav acknowledged what she called the hypocrisy of Norway’s drive to reduce greenhouse gases while producing lots of oil and gas. Fossil-fuel exports generated revenue of $180 billion last year. “We’re exporting that pollution,” Ms. Stav said, noting that her party has called for oil and gas production to be phased out by 2035.

But Norway’s government has not pulled back on oil and gas production. “We have several fields in production, or under development, providing energy security to Europe,” Amund Vik, state secretary in the Norwegian Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, said in a statement.

Elsewhere, Norway’s power grid has held up fine even with more demand for electricity. It helps that the country has abundant hydropower. Even so, electric vehicles have increased the demand for electricity modestly, according to calculations by the E.V. Association, and most owners are charging cars at night, when demand is lower and power is cheaper.

Elvia, which supplies electricity to Oslo and the surrounding area, has had to install new substations and transformers in some places, said Anne Nysæther, the company’s managing director. But, she added, “we haven’t seen any issue of the grid collapsing.”

Storage is one of the significant challenges of electrifying an economy using the cleanest power widely available, solar and wind. Unlike fossil fuels, nuclear, geothermal, and hydropower, solar and wind provide power intermittently. Smoothing the different production/demand curves requires storing that energy somewhere until it’s needed. What if you could harness hydropower as a battery?

New research released Tuesday by Global Energy Monitor reveals a transformation underway in hydroelectric projects — using the same gravitational qualities of water, but typically without building large, traditional dams like the Hoover in the American West or Three Gorges in China. Instead, a technology called pumped storage is rapidly expanding.

These systems involve two reservoirs: one on top of a hill and another at the bottom. When electricity generated from nearby power plants exceeds demand, it’s used to pump water uphill, essentially filling the upper reservoir as a battery. Later, when electricity demand spikes, water is released to the lower reservoir through a turbine, generating power.

Pumped storage isn’t a new idea. But it is undergoing a renaissance in countries where wind and solar power are also growing, helping allay concerns about weather-related dips in renewable energy output.

In addition to power production/transmission challenges, charging infrastructure needs a lot of work. Interstate routes are largely covered in the US, but local infrastructure can still be hard to find and busy in areas with high EV adoption rates. In Norway, service stations have been learning lessons and adapting because they know, at some point, they’ll have to.

Circle K, which bought gas stations that had belonged to a Norwegian government-owned oil company, is using the country to learn how to serve electric car owners in the United States and Europe. The chain, now owned by Alimentation Couche-Tard, a company based near Montreal, has more than 9,000 stores in North America.

Guro Stordal, a Circle K executive, has the difficult task of developing charging infrastructure that works with dozens of vehicle brands, each with its own software.

Electric vehicle owners tend to spend more time at Circle K because charging takes longer than filling a gasoline tank. That’s good for food sales. But gasoline remains an important source of revenue.

“We do see it as an opportunity,” Hakon Stiksrud, Circle K's head of global e-mobility, said of electric vehicles. “But if we are not capable of grasping those opportunities, it quickly becomes a threat.”

Until that kind of transformation occurs, EV owners rely on personal chargers for their day-to-day needs. This works well for people with driveways and garages, but what about apartment and condo dwellers? In Colorado, HB23-1233 is currently sitting on the governor’s desk. It builds on existing laws to further limits the ability of HOAs and condo associations to make it difficult to charge an EV, along with several other provisions to encourage a broader range of charging possibilities.

Concerning energy efficiency, and, in connection therewith, requiring the state electrical board to adopt rules facilitating electric vehicle charging at multifamily buildings, limiting the ability of the state electrical board to prohibit the installation of electric vehicle charging stations, forbidding private prohibitions on electric vehicle charging and parking, requiring local governments to count certain spaces served by an electric vehicle charging station for minimum parking requirements, forbidding local governments from prohibiting the installation of electric vehicle charging stations, exempting electric vehicle chargers from business personal property tax, and authorizing electric vehicle charging systems along highway rights-of-way.

What about locations where only street parking is available? Curbside charging is needed, but no one has yet figured out a model that works. A Brooklyn-based startup, itselectric, in conjunction with NYCEDC and Hyundai, is working on one approach to allow property owners with excess electrical capacity to host curbside chargers and make money from them.

"The United States has high goals for electric vehicle adoption, but the country is not currently prepared for what this means in terms of accessible charging," said Nathan King, CEO & Co-Founder of itselectric. "Our technology is specifically built for cities to ensure that every community—no matter the median income or prevalence of driveways and garages—has access to clean transportation."

In a brief Brooklyn clean-tech startup aside, Kelvin (formerly Radiator Labs), the company my cousin Marshall Cox started a decade or so ago to commercialize a steam radiator “Cozy” that helps to regulate temperature and save energy, recently raised $30 million to expand into Europe and heat pumps. Congrats Marshall!

Back to EVs and my quest for a new vehicle. In a post-pandemic remote-work world, what do I need a car for anyways? In the last three years, I’ve driven less than 4,000 miles total when I was doing 12,000+ a year prior, and the trip lengths are much shorter. And if I do get a new vehicle, I’ll want it to last another 20 years. I’m suffering from a bit of paralysis by analysis, trying to figure it out.

With most of my weekly errands within a mile or two of home, I could get away with a cargo bike and have been trying, without luck, to take advantage of Denver’s E-Bike rebates. That program has been wildly successful, and the General Assembly recently decided to take a similar approach state-wide.

Under legislation approved by state lawmakers earlier this week, residents at any income level could get a $450 tax rebate toward an e-bike purchase beginning in the spring of 2024. The legislation also doesn’t restrict combining the rebate with other local e-bike incentives like Denver’s.

"Electric bicycles are a great option to replace short car trips," said Will Toor, the director of the Colorado Energy Office. "This bill will also play a big role in improving air quality, promoting active lifestyles and saving Coloradans money on fuel costs.”

Rebates are a great way to encourage EV adoption, but I have to point out that the IRS and Department of Energy dropped the ball with the execution of recent changes to the federal EV rebate.

About 80 percent of people who were shopping for an electric vehicle recently surveyed by Cars.com said tax credits played a big role in their decision to buy an electric car and the vehicle they planned to buy.

Many industry experts and consumers have praised the multipronged mission of the law to curb greenhouse gas emissions, create jobs in the United States and blunt China’s dominance in batteries and mineral processing. Since President Biden took office, automakers, battery and other companies have announced plans to spend more than $100 billion to electrify the U.S. auto industry.

Yet the rules could hinder the goal of getting more people to buy electric vehicles — at least for the next few years.

“They made it complex for a reason, but in the meantime it’s creating all kinds of chaos for consumers,” said Chris Harto, senior policy analyst for Consumer Reports. “In the short term, it’s absolutely going to hurt the companies that aren’t eligible and help the companies that are.”

Chaos certainly describes my experience. I had been planning on a Volkswagen id.4 arriving in January. However, ongoing production delays as they ramped up their US production kept pushing out the date, and it’s still unclear to me if it’s eligible for the rebate. This forced pause was welcome, though, since it brought me back to my earlier question, what do I need an EV for?

Given the continued prospect of my job not requiring a commute (and if it starts to again, I may decide not to take them up on that) and the possibility of a cargo bike filling my local errand needs, the only thing I need a vehicle for is touring around Colorado.

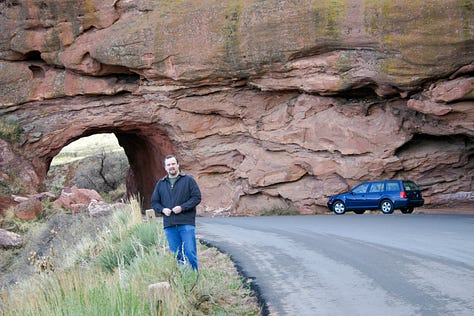

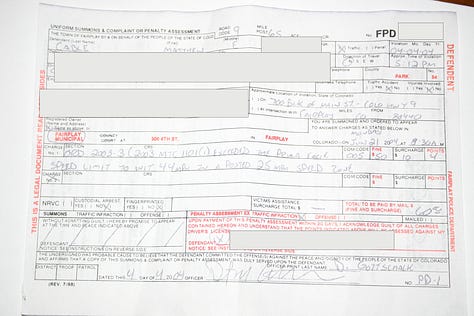

One of the first things I did when I got my new car back in 2004 was take it for a ride up in the mountains, down 285, through Fairplay - where it was inaugurated with the requisite speeding ticket - over Hoosier Pass to Breckenridge and back to Denver. I love driving around in the mountains. I also love camping, but my increasingly old bones no longer enjoy sleeping on the ground. All this leads me to think I should be looking at something I can camp with, suitable for driving around in the mountains, and that I can use for occasional, longer-distance errands.

I’m leaning towards an AWD EV or PHEV pickup, SUV, or van, but the pickings are slim, and availability is low. I’ve had a reservation on a Rivian R1S for almost a year now with no sign of movement, an already high price rising, and a company that seems increasingly unlikely to be around for the next 20 years. I’ve looked at the Ford Lightning F-150, but it’s a little on the large side to fit in my parking situation, and its availability is nonexistent. Most of the PHEV pickup and SUV options aren’t AWD. Options are effectively absent for vans. There’s a local company, Lightning eMotors which does commercial conversions, but nothing an individual could buy, and they seem to have an uncertain future. With the arrival of the Ford e-Transit and Mercedes-Benz eSprinter, base models for all sorts of camping van conversions, I hope electric camper options appear.

The next few years should see a steady rollout of EV options from major manufacturers and steady improvement to the charging infrastructure. And so I will wait a little longer, hoping things shake out a bit more. My TDI has made almost 20 years; it can survive a few more.